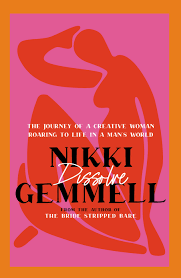

Author: Nikki Gemmell

Title: Dissolve

Publisher: Hachette Australia, 2021; RRP $29.99

Nikki Gemmell has written 13 works of fiction and four non-fiction including the initially anonymous The Bride Stripped Bare, and is popular in Australia and internationally for the originality and honesty of her voice, for ‘saying the things that women think but do not say’. She also worked extensively in media, including writing a column for the Weekend Australian Magazine.

In Dissolve, an autobiographical novel, an important role is played by a position she also held in real life working for a small radio station in Alice Springs.

Dissolve is also the story of a loving relationship which falters. The author is deeply infatuated with a man identified throughout simply as ‘W’. She leaves her job and the people she enjoyed working with in Alice Springs to join himm only for him to tell her barely days before their wedding that he is having doubts.

We are told this in the first chapter. At the same time the author segues neatly into what will be a parallel theme throughout the work as she struggles through the following days processing this: looking back on her own life, the relationship itself, and frequently referencing the life stories of other women writers. In the process, she uncovers how love and marriage impact on the creative life of women.

Near the beginning she writes,

‘W is at the heart of this story, as men so often are. Back then you were the sidekick. The experiment. Accessory. Muse. As women so often are. But finally you are writing this out, centring yourself in the narrative,…’ (p18) (my italics)

Dissolve moves back and forth in time from initial attraction and burgeoning passion to that fatal conversation after she leaves Alice Springs to begin living with W, who does not want to move. His is a city soul. The book’s central focus is what she discovers in the process of trying to put herself back together. Part of it is how she realises how girls learn early the power men hold over their lives – ignited by that moment when W tells her ‘he couldn’t go through with it’ – that ‘the money thing between you is too uncertain’.

The ‘money thing’ being that the author is the regular wage earner in the relationship and there had been no indication this state of affairs would not continue. Even before his bombshell this had been a lurking concern, but one she left unspoken until only days before, when she had finally brought it up.

She lets him know she is concerned about what her role in the relationship will be once they are married – her job in Alice Springs is hugely demanding and she replaces it with another equally demanding one when she moves to the city. He, on the other hand, does not have a regular job, which means she will be the breadwinner. So where in the relationship will fit her dream of being a writer?

Thinking about it afterwards, however, still loving him and knowing absolutely that he loves her, she finds herself unable to contemplate his absence or the thought of losing their shared vision of a future home and family together.

via hachette, 2020

In her turmoil she looks back on and liberally quotes the voices found in letters and diaries and in biographical works of a wide range of individual women writers, along with details from recorded history of other relationships between women creatives and male artists.

She explores for example the relationships of such couples as Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, and our own Charmian Clift and George Johnston, through the lens of her relationship with W. The narrative takes the form almost of a helpless pull between a deeply enamoured self torn by pain and confusion as she struggles to find her place, and a more dispassionate self reflecting on what she finds about other women’s struggles to maintain their creative life within relationships with male creative partners. Interestingly, she also includes a relationship between two women where one’s creative life is subsumed by that of her more strongly socially positioned partner.

Gemmell discovers a ‘joking’ manifesto poet Ted Hughes wrote for second wife Assia Wevill, successful in her job and an aspiring poet. His list includes: full responsibility of the care of his three children; no cooking by him; one ‘new’ meal a week; a daily log of expenses and ‘acceptance of all Hughes friends’ (p184)., No woke woman would be able to hear that list without a slight chill.

Dissolve is written in a chatty, reflective and explorative voice. The writing style is quick and entertaining, changing depending on whether she is reliving the relationship or looking back with concern, anger and grief. When describing her times with W the sentences are short, breathy, deliriously happy, almost like a conversation with the reader as a confidante over coffee. Those expressing her doubts and trying to understand what she is feeling are longer, thoughtful and of a woman totally in control of herself and her life.

Towards the end she reaches the conclusion that, despite where love might take them, in order to follow the demands of her art, a woman needs a partner who she knows will be mutually supportive. And that, she concludes wryly, includes a man ‘comfortable with ironing his own shirts’ (p199).

Dissolve to me was at its heart the story of a very real relationship and of what it costs to follow a dream.

Reviewed by: Rhonda Cotsell, December 2021

Ballarat Writers Inc. Book Review Group

Review copy provided by the publisher

.

Leave a Reply