You know one when you read it. The moment when you are forced to stop scanning words in order to just sit and digest the beauty of the sentence you have just read. Not long ago, I attended Emily Bitto’s course ‘Exquisite Sentences’ at Writers Victoria. Emily Bitto is an acclaimed author, and I love the fact that through Writers Victoria you can be one of only a handful of people sitting with, and learning from, authors of such a calibre!

Emily was a warm and approachable speaker, who provided nuggets of wisdom throughout the whole afternoon. She provided unique writing activities and drills to encourage playfulness in our writing. Creating exquisite sentences is often a role of editing; for example, reading carefully for clichés which she stated are the enemy of original, exquisite sentences. When I got home and reflected on cliché, I found my writing was overflowing with them, they were a dime-a-dozen, in fact they were packed like sardines into the manuscript (clearly, I have a penchant for clichés and puns!) But it was a useful discussion to have in mind as I embarked on the editing of my latest work.

Emily also focused heavily on the importance of verbs in our writing. Often overlooked, an interesting verb can bring a spark to your sentence and elevate it to exquisite. We practised strange combinations of verbs and nouns. I had a crow which slaughtered the quiet of the morning and a river which hauled itself through the land. Approaching writing with a sense of fun and experimentation was part of the appeal, as often I find myself getting bogged down with ‘serious’ writing. It was also an easy pick-up, as I edited, to find verbs which I could strengthen throughout each of the chapters.

I encourage you to look through the wide range of courses on offer with Writers Victoria. Some are offered online, which is convenient for regional and rural writers, but the experience of sitting in a room with other writers is almost as valuable as the course itself! I’ve always been a strong reader, but since working with Emily, I’ve taken to reading and enjoying more poetry, which allows me to feel the rhythm of words more clearly. I’m revelling in their pleasure once again.

Things to do to encourage more exquisite sentences:

- Expand your vocabulary and collect words

- Read constantly and widely

- Read poetry

- Write more (every day!)

- Spend time writing to experiment and play, rather than for completing a ‘project’.

- Recognise and cultivate your own unique way of looking at the world—your most valuable tool as a writer.

by Nicole Kelly, BWI member

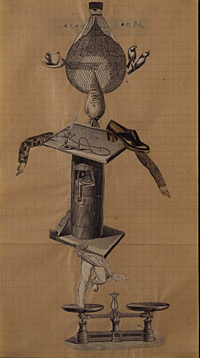

Image: Exquisite Corpse (1938) André Breton, Jacqueline Lamba, Yves Tanguy